Chapter 10: Retina

DISEASES OF THE PERIPHERAL RETINA

RETINAL DETACHMENT

The term "retinal detachment" denotes separation of the sensory retina, ie, the photoreceptors and inner tissue layers, from the underlying retinal pigment epithelium. There are three main types: rhegmatogenous detachment, traction detachment, and serous or hemorrhagic detachment.

1. RHEGMATOGENOUS RETINAL DETACHMENT

The most common of the three major types of retinal detachments is rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. The characteristics of a rhegmatogenous detachment are a full-thickness break (a "rhegma") in the sensory retina, variable degrees of vitreous traction, and passage of liquefied vitreous through the sensory retinal defect into the subretinal space. A spontaneous rhegmatogenous retinal detachment is usually preceded or accompanied by a posterior vitreous detachment. Myopia, aphakia, lattice degeneration, and ocular trauma are associated with this type of retinal detachment. Binocular indirect ophthalmoscopy with scleral depression (![]() Figures 2-16 and

Figures 2-16 and ![]() 2-18) reveals elevation of the translucent detached sensory retina. A careful search usually reveals one or more full-thickness sensory retinal breaks such as a horseshoe tear, round atrophic hole, or anterior circumferential tear (retinal dialysis). The location of retinal breaks varies according to type; horseshoe tears are most common in the superotemporal quadrant, atrophic holes in the temporal quadrants, and retinal dialysis in the inferotemporal quadrant. When multiple retinal breaks are present, the defects are usually within 90 degrees of one another.

2-18) reveals elevation of the translucent detached sensory retina. A careful search usually reveals one or more full-thickness sensory retinal breaks such as a horseshoe tear, round atrophic hole, or anterior circumferential tear (retinal dialysis). The location of retinal breaks varies according to type; horseshoe tears are most common in the superotemporal quadrant, atrophic holes in the temporal quadrants, and retinal dialysis in the inferotemporal quadrant. When multiple retinal breaks are present, the defects are usually within 90 degrees of one another.

Treatment

Scleral buckling or pneumatic retinopexy are the two most popular and effective surgical techniques for the repair of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Each procedure requires careful localization of the retinal break and treatment with cryotherapy or laser in order to create an adhesion between the pigment epithelium and the sensory retina. With scleral buckling surgery, the retinal break is mounted on sclera indented by an explant. The scleral indentation can be achieved by a variety of techniques and materials, each of which has inherent advantages and disadvantages. Pneumatic retinopexy involves the intraocular injection of air or an expandable gas in order to tamponade the retinal break while the chorioretinal adhesion forms. An overall reattachment rate of 90% is reported; however, the visual results are dependent on the preoperative status of the macula. If the macula is involved in rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the likelihood of complete visual recovery is slight.

2. TRACTION RETINAL DETACHMENT

Traction retinal detachment is the second most common type and is most commonly due to proliferative diabetic retinopathy, proliferative vitreoretinopathy, retinopathy of prematurity, or ocular trauma. In contrast to the convex appearance of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment, the typical traction retinal detachment has a more concave surface and is likely to be more localized, usually not extending to the ora serrata. The tractional forces that actively pull the sensory retina away from the underlying pigment epithelium are caused by a clinically apparent vitreal, epiretinal, or subretinal membrane consisting of fibroblasts and of glial and retinal pigment epithelial cells. In diabetic traction retinal detachment, vitreous contraction draws the fibrovascular tissue and underlying retina anteriorly toward the vitreous base. Initially the detachment may be localized along the vascular arcades, but progression may spread to involve the midperipheral retina and the macula. Proliferative vitreoretinopathy is a complication of rhegmatogenous retinal detachment and is the most common cause of failure of surgical repair in these eyes.

The basic pathologic process in eyes with proliferative vitreoretinopathy is growth and contraction of cellular membranes on both sides of the retina and on the posterior vitreous surface. Focal traction from cellular membranes can produce a retinal tear and lead to combined tractional-rhegmatogenous retinal detachment.

Treatment

The primary treatment of traction retinal detachment is vitreoretinal surgery and may involve vitrectomy, membrane removal, scleral buckling, and injection of intraocular gas or silicone oil.

3. SEROUS & HEMORRHAGIC RETINAL DETACHMENT

Serous and hemorrhagic retinal detachment can occur in the absence of either retinal break or vitreoretinal traction. These detachments are the result of a collection of fluid beneath the sensory retina and are caused primarily by diseases of the retinal pigment epithelium and choroid. Degenerative, inflammatory, and infectious diseases limited to the macula, including the multiple causes of subretinal neovascularization, may be associated with this third type of retinal detachment and are described in an earlier section of this chapter. This type of detachment may also be associated with systemic vascular and inflammatory disease as described in Chapters 7 and 15.

RETINOPATHY OF PREMATURITY

Retinopathy of prematurity is a vasoproliferative retinopathy that is the leading cause of childhood blindness in the United States and a major cause of blindness throughout the developed world. An international classification of this disease divides the retina into three zones and characterizes the extent of disease by the number of clock hours involved; the retinal changes are divided into five stages described in Table 10-2.

The demarcation line is a narrow white band that marks the junction of vascular and avascular retina in stage 1; it is the first definite ophthalmoscopic sign of retinopathy of prematurity. As this band increases in height, width, and volume and rises up from the plane of the retina, the ridge of stage 2 is seen. Neovascular proliferation along the posterior aspect of the ridge and extending into the vitreous defines stage 3. Stage 4 is characterized by subtotal retinal detachment, and the clinical sign of stage 5 is a funnel-shaped total retinal detachment.

Treatment

The treatment of retinopathy of prematurity is based on the classification and stage of the disease. It is important to note that a significant number of patients with retinopathy of prematurity undergo spontaneous regression. Peripheral retinal changes of regressed retinopathy of prematurity include avascular retina, peripheral folds, and retinal breaks; associated changes in the posterior pole may include straightening of the temporal vessels, temporal stretching of the macula, and retinal tissue that appears to be dragged over the disk (Figure 10-18). Other ocular findings of regressed retinopathy of prematurity include myopia (which may be asymmetric), strabismus, cataract, and angle-closure glaucoma.

Figure 10-18: Retinopathy of prematurity with stretching of the macula and straightening of retinal vessels.

While stage 1 and stage 2 disease require nothing more than observation, transscleral cryotherapy or laser photocoagulation to the avascular retina should be considered in eyes with stage 3 disease. Vitreoretinal surgery as described above in the section on traction retinal detachment may be appropriate for eyes with stage 4 or stage 5 disease. The etiology and treatment of retinopathy of prematurity as well as the recommended screening protocols are discussed in Chapter 17.

RETINAL DEGENERATIONS

This group of disorders encompasses a number of diseases with various ocular and, in some instances, systemic manifestations. In this section, several specific disorders will be used as prototypes with which to understand the major characteristics of retinal degenerations.

Retinitis Pigmentosa

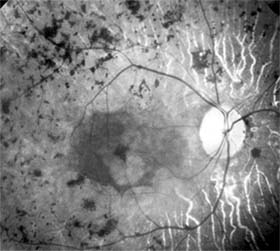

Retinitis pigmentosa is a group of hereditary retinal degenerations characterized by progressive dysfunction of the photoreceptors and associated with progressive cell loss and eventual atrophy of several retinal layers. The typical form of this disease can be inherited as an autosomal recessive, autosomal dominant, or X-linked recessive trait; one-third of cases will have a negative family history. The hallmark symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa are night blindness (nyctalopia) and gradually progressive peripheral visual field loss. The most characteristic ophthalmoscopic findings are narrowing of the retinal arterioles, mottling of the retinal pigment epithelium, and peripheral retinal pigment clumping, referred to as "bone-spicule formation" (Figure 10-19). While retinitis pigmentosa is a generalized photoreceptor disorder, in most cases rod function is more severely affected, leading to subjective sensations associated with poor scotopic function. The electroretinogram usually shows either markedly reduced or absent retinal function; the electro-oculogram lacks the usual light rise. The fundus appearance of retinitis pigmentosa may be mimicked by several disorders, including chorioretinitis, trauma, vascular occlusion, and resolved retinal detachment.

Figure 10-19: Retinitis pigmentosa with arteriolar narrowing and peripheral retinal pigment clumping.

The effects of supplemental vitamins on the progression of retinitis pigmentosa require further study before treatment recommendations can be made. Patients with the disease benefit from genetic counseling and appropriate referral to agencies that provide services to the visually impaired.

Leber's Congenital Amaurosis

Leber's congenital amaurosis is a group of disorders characterized by severe visual impairment or blindness from infancy with no discernible cause. The disorders are usually inherited in an autosomal recessive manner and may be associated with mental retardation, seizures, and renal or muscular abnormalities. The ophthalmoscopic findings are variable; most patients show either a normal fundus appearance or only subtle retinal pigment epithelial granularity and mild vessel attenuation. A markedly reduced or absent electroretinogram indicates generalized photoreceptor dysfunction, and in infants this test is the only method by which an absolute diagnosis can be made.

Gyrate Atrophy

Gyrate atrophy is an autosomal recessive disorder caused by reduced activity of ornithine aminotransferase, a mitochondrial matrix enzyme that catalyzes several amino acid pathways. The incidence of this disorder is relatively high in Finland, and the ophthalmologic features are the most prominent manifestations of the disease. Patients usually develop nyctalopia within the first decade of life, and progressive peripheral visual field loss follows. Characteristic sharply demarcated circular areas of chorioretinal atrophy develop in the midperiphery of the fundus during the teenage years and become confluent with macular involvement late in the course of the disease. The electroretinogram is decreased or absent, and the electro-oculogram is reduced.

Treatment approaches to this disease have included pyridoxine supplementation, restriction of dietary arginine, and supplemental dietary lysine.

Peripheral Chorioretinal Atrophy

Peripheral chorioretinal atrophy (paving stone degeneration) is a common chorioretinal degeneration found in nearly one-third of adult eyes. Ophthalmoscopically, the lesions appear as isolated or grouped, small, discrete, yellow-white areas with prominent underlying choroidal vessels and pigmented borders. Choroidal vascular insufficiency is thought to be the cause of this benign disorder because the pathologic changes are limited to that portion of the retina supplied by the choriocapillaris. Paving stone degeneration is not of great pathologic significance, though it may be a sign of peripheral vascular disease.

Lattice Degeneration

Lattice degeneration is the most common of the inherited vitreoretinal degenerations, with an estimated incidence of 7% of the general population. Lattice degeneration is more commonly found in myopic eyes and is frequently associated with retinal detachment, occurring in nearly one-third of retinal detachment patients. The ophthalmoscopic appearance may be that of localized round, oval, or linear retinal thinning, with pigmentation, branching white lines, and whitish-yellow flecks; the hallmarks of the disease are the thinned retina punctuated by sharp borders with firm vitreoretinal adhesions at the margins. The mere presence of lattice degeneration is not cause enough for prophylactic therapy. A strong family history of retinal detachments, retinal detachment in the fellow eye, high myopia, and aphakia are risk factors for retinal detachment in eyes with lattice degeneration, and prophylactic treatment with cryosurgery or laser photocoagulation may be warranted.

RETINOSCHISIS

Degenerative retinoschisis, unlike X-linked juvenile retinoschisis described above, is a common acquired peripheral retinal disorder that is believed to develop from preexisting peripheral cystoid degeneration. The cystic changes of peripheral cystoid degeneration are seen to some degree in virtually all adults. This cystoid degeneration is characterized by intraretinal microcysts that often coalesce, giving the appearance of lobulated, irregularly branching, tortuous channels. Peripheral cystoid degeneration may develop into either of two degenerative forms of retinoschisis, each of which is characterized by sharply demarcated and absolute visual field defects.

Typical degenerative retinoschisis occurs in 1% of adults and is a bilateral disease in one-third of affected patients. On clinical examination, the disorder appears as a round or ovoid area of retinal splitting with fusiform elevation of the inner layer and an optically empty schisis cavity. The retinal splitting occurs at the outer plexiform layer. Complications such as hole formation and marked posterior extension are very uncommon and rarely require treatment.

Reticular degenerative retinoschisis is characterized by round or oval areas of retinal splitting in which a bullous elevation of an extremely thin inner layer occurs, most commonly in the lower temporal quadrant. In this form of the disease, the splitting usually occurs in the nerve fiber layer, and typical peripheral cystoid degeneration is usually present anterior to the lesion. When retinal breaks are present in both the inner and the outer layers, progressive rhegmatogenous retinal detachment may develop and threaten the macula, thus requiring treatment.

PREVIOUS | NEXT

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9

10.1036/1535-8860.ch10