Chapter 5: Conjunctiva

CONJUNCTIVITIS DUE TO INFECTIOUS AGENTS

The types of conjunctivitis and their commonest causes are set forth in Tables 5-1 and 5-2.

Because of its location, the conjunctiva is exposed to many microorganisms and other stressful environmental factors. Several mechanisms protect the surface of the eye from external substances: In the tear film, the aqueous component dilutes infectious material, mucus traps debris, and a pumping action of the lids constantly flushes the tears to the tear duct; the tears contain antimicrobial substances, including lysozyme and antibodies (IgG and IgA).

Common pathogens that can cause conjunctivitis include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Staphylococcus aureus, Neisseria meningitidis, most human adenovirus strains, herpes simplex virus type 1 and type 2, and two picornaviruses. Two sexually transmitted agents that cause conjunctivitis are Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae.

Cytology of Conjunctivitis

Damage to the conjunctival epithelium by a noxious agent may be followed by epithelial edema, cellular death and exfoliation, epithelial hypertrophy, or granuloma formation. There may also be edema of the conjunctival stroma (chemosis) and hypertrophy of the lymphoid layer of the stroma (follicle formation). Inflammatory cells, including neutrophils, eosinophils, basophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells, may be seen and often indicate the nature of the damaging agent. The inflammatory cells migrate from the conjunctival stroma through the epithelium to the surface. They then combine with fibrin and mucus from the goblet cells to form the conjunctival exudate, which is responsible for the "mattering" on the lid margins (especially in the morning).

The inflammatory cells appear in the exudate or in scrapings taken with a sterile platinum spatula from the anesthetized conjunctival surface. The material is stained with Gram's stain (to identify the bacterial organisms) and with Giemsa's stain (to identify the cell types and morphology). A predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes is characteristic of bacterial conjunctivitis. Generally, a predominance of mononuclear cells-especially lymphocytes-is characteristic of viral conjunctivitis. If a pseudomembrane or true membrane is present (eg, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis or herpes simplex virus conjunctivitis), neutrophils then predominate because of coexistent necrosis. In chlamydial conjunctivitis, neutrophils and lymphocytes are usually present in equal numbers.

In allergic conjunctivitis, eosinophils and basophils are frequently present in conjunctival biopsies, but they are less common on conjunctival smears; eosinophils or eosinophilic granules are commonly found in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. High levels of proteins secreted by eosinophils (eg, eosinophil cationic protein) can be found in the tears of patients with vernal, atopic, or allergic conjunctivitis. Eosinophils and basophils are found in allergic conjunctivitis, and scattered eosinophilic granules and eosinophils are found in vernal keratoconjunctivitis. In all types of conjunctivitis, there are plasma cells in the conjunctival stroma. They do not migrate through the epithelium, however, and are therefore not seen in smears of exudate or of scrapings from the conjunctival surface unless the epithelium has become necrotic, as it may in trachoma; in this event, the rupturing of a follicle allows the plasma cells to reach the epithelial surface. Since the mature follicles of trachoma rupture easily, the finding of large, pale-staining lymphoblastic (germinal center) cells in scrapings strongly suggests trachoma.

Symptoms of Conjunctivitis

The important symptoms of conjunctivitis are a foreign body sensation, a scratching or burning sensation, a sensation of fullness around the eyes, itching, and photophobia.

Foreign body sensation and a scratching or burning sensation are often associated with the swelling and papillary hypertrophy that normally accompany conjunctival hyperemia. If there is pain, the cornea is probably also affected. Pain of the iris or ciliary body is also suggestive of corneal involvement.

Signs of Conjunctivitis (Table 5-2)

The important signs of conjunctivitis are hyperemia, tearing, exudation, pseudoptosis, papillary hypertrophy, chemosis, follicles, pseudomembranes and membranes, granulomas, and preauricular adenopathy.

Hyperemia is the most conspicuous clinical sign of acute conjunctivitis. The redness is most marked in the fornix and diminishes toward the limbus by virtue of the dilation of the posterior conjunctival vessels. (A perilimbal dilation or ciliary flush suggests inflammation of the cornea or deeper structures.) A brilliant red suggests bacterial conjunctivitis, and a milky appearance suggests allergic conjunctivitis. Hyperemia without cellular infiltration suggests irritation from physical causes such as wind, sun, smoke, etc, but may occur occasionally with diseases associated with vascular instability (eg, acne rosacea).

Tearing (epiphora) is often prominent in conjunctivitis, the tears resulting from the foreign body sensation, the burning or scratching sensation, or the itching. Mild transudation also arises from the hyperemic vessels and adds to the tearing. An abnormally scant secretion of tears and an increase in mucous threads suggests keratoconjunctivitis sicca.

Exudation is a feature of all types of acute conjunctivitis. The exudate is flaky and amorphous in bacterial conjunctivitis and stringy in allergic conjunctivitis. "Mattering" of the eyelids occurs upon awakening in almost all types of conjunctivitis, and if the exudate is copious and the lids are firmly stuck together, the conjunctivitis is probably bacterial or chlamydial.

Pseudoptosis is a drooping of the upper lid secondary to infiltration of Müller's muscle. The condition is seen in several types of severe conjunctivitis, eg, trachoma and epidemic keratoconjunctivitis.

Papillary hypertrophy is a nonspecific conjunctival reaction that occurs because the conjunctiva is bound down to the underlying tarsus or limbus by fine fibrils. When the tuft of vessels that forms the substance of the papilla (along with cellular elements and exudates) reaches the basement membrane of the epithelium, it branches over the papilla like the spokes in the frame of an umbrella. An inflammatory exudate accumulates between the fibrils, heaping the conjunctiva into mounds. In necrotizing disease (eg, trachoma), the exudate may be replaced by granulation tissue or connective tissue.

When the papillae are small, the conjunctiva usually has a smooth, velvety appearance. A red papillary conjunctiva suggests bacterial or chlamydial disease (eg, a velvety red tarsal conjunctiva is characteristic of acute trachoma). With marked infiltration of the conjunctiva, giant papillae form which are flat-topped, polygonal, and milky-red in color. On the upper tarsus, they suggest vernal keratoconjunctivitis and giant papillary conjunctivitis with contact lens sensitivities; on the lower tarsus, they suggest atopic keratoconjunctivitis. Giant papillae may also occur at the limbus, especially in the area that is normally exposed when the eyes are open (between 2 and 4 o'clock and between 8 and 10 o'clock). Here they appear as gelatinous mounds that may encroach on the cornea. Limbal papillae are characteristic of vernal keratoconjunctivitis but are rare in atopic keratoconjunctivitis.

Chemosis of the conjunctiva strongly suggests acute allergic conjunctivitis but may also occur in acute gonococcal or meningococcal conjunctivitis and especially in adenoviral conjunctivitis. Chemosis of the bulbar conjunctiva is seen in patients with trichinosis. Occasionally, chemosis may appear before there is any gross cellular infiltration or exudation.

Follicles are seen in most cases of viral conjunctivitis, in all cases of chlamydial conjunctivitis except neonatal inclusion conjunctivitis, in some cases of parasitic conjunctivitis, and in some cases of toxic conjunctivitis induced by topical medications such as idoxuridine, dipivefrin, and miotics. Follicles in the inferior fornix and at the tarsal margins have limited diagnostic value, but when they are located on the tarsi (especially the upper tarsus), chlamydial, viral, or toxic conjunctivitis (following topical medication) should be suspected.

The follicle consists of a focal lymphoid hyperplasia within the lymphoid layer of the conjunctiva and usually contains a germinal center. Clinically, it can be recognized as a rounded, avascular white or gray structure. On slitlamp examination, small vessels can be seen arising at the border of the follicle and encircling it.

Pseudomembranes and membranes are the result of an exudative process and differ only in degree. A pseudomembrane is a coagulum on the surface of the epithelium, and when it is removed the epithelium remains intact. A membrane is a coagulum involving the entire epithelium, and if it is removed a raw, bleeding surface remains. Pseudomembranes or membranes may accompany epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, primary herpes simplex virus conjunctivitis, streptococcal conjunctivitis, diphtheria, cicatricial pemphigoid, and erythema multiforme major. They may also be an aftermath of chemical burns, especially alkali burns.

Ligneous conjunctivitis is a peculiar form of recurring membranous conjunctivitis. It is bilateral, seen mainly in children, predominantly in females, and may be associated with other systemic findings, including nasopharyngitis and vulvovaginitis.

Granulomas of the conjunctiva always affect the stroma and most commonly are chalazia. Other endogenous causes include sarcoid, syphilis, cat-scratch disease, and, rarely, coccidioidomycosis. Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome includes conjunctival granulomas and a prominent preauricular lymph node, and this group of diseases may require biopsy examination to secure diagnosis.

Phlyctenules represent a delayed hypersensitivity reaction to microbial antigen, eg, staphylococcal or mycobacterial antigens. Phlyctenules of the conjunctiva initially consist of a perivasculitis with lymphocytic cuffing of a vessel. When they progress to ulceration of the conjunctiva, the ulcer bed has many polymorphonuclear leukocytes.

Preauricular lymphadenopathy is an important sign of conjunctivitis. A grossly visible preauricular node is seen in Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome and, rarely, in epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. A large or small preauricular node, sometimes slightly tender, occurs in primary herpes simplex conjunctivitis, epidemic keratoconjunctivitis, inclusion conjunctivitis, and trachoma. Small but nontender preauricular lymph nodes occur in pharyngoconjunctival fever and acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. Occasionally, preauricular lymphadenopathy may be observed in children with infections of the meibomian glands.

BACTERIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Two forms of bacterial conjunctivitis are recognized: acute (and subacute) and chronic. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis may be self-limited when caused by certain microorganisms such as Haemophilus influenzae. The course may take up to 2 weeks if proper treatment is not given.

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis may become chronic. Treatment with one of the many available antibacterial agents usually cures the condition in a few days.

Purulent conjunctivitis caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Neisseria meningitidis may lead to serious ocular complications if not treated early.

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs:

The organisms listed in Table 5-1 account for most cases of bacterial conjunctivitis. They produce bilateral irritation and injection, a purulent exudate with sticky lids on waking, and occasionally lid edema. The infection usually starts in one eye and is spread to the other by the hands. It may be spread from one person to another by fomites.

1. Hyperacute (and subacute) bacterial conjunctivitis-Purulent conjunctivitis-

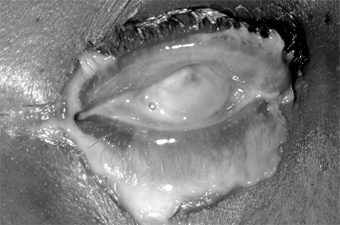

(caused by N gonorrhoeae, Neisseria kochii, and N meningitidis) is marked by a profuse purulent exudate (Figure 5-1). Meningococcal conjunctivitis may occasionally be seen in children. Any severe, profusely exudative conjunctivitis demands immediate laboratory investigation and immediate treatment. If there is any delay, there may be severe corneal damage or loss of the eye, or the conjunctiva could become the portal of entry for either N gonorrhoeae or N meningitidis, leading to septicemia or meningitis.

Figure 5-1: Gonococcal conjunctivitis. Profuse purulent exudate. (Courtesy of L Schwab.)

Acute mucopurulent (catarrhal) conjunctivitis often occurs in epidemic form and is called "pinkeye" by most laymen. It is characterized by an acute onset of conjunctival hyperemia and a moderate amount of mucopurulent discharge. The commonest causes are Streptococcus pneumoniae in temperate climates and Haemophilus aegyptius in warm climates. Less common causes are staphylococci and other streptococci. The conjunctivitis caused by S pneumoniae and H aegyptius may be accompanied by subconjunctival hemorrhages. H aegyptius conjunctivitis in Brazil has been followed by a fatal purpuric fever produced by a plasmid-associated toxin of the bacteria.

Subacute conjunctivitis is caused most often by H influenzae and occasionally by Escherichia coli and Proteus species. H influenzae infection is characterized by a thin, watery, or flocculent exudate.

2. Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis-Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis-

occurs in patients with nasolacrimal duct obstruction and chronic dacryocystitis, which are usually unilateral. It may also be associated with chronic bacterial blepharitis or meibomian gland dysfunction. Patients with floppy lid syndrome or ectropion may develop secondary bacterial conjunctivitis.

Rare bacterial conjunctivitides may be caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Streptococcus pyogenes. Pseudomembranes or membranes caused by these organisms may form on the palpebral conjunctiva. The rare cases of chronic conjunctivitis produced by Moraxella catarrhalis, the coliform bacilli, Proteus, etc, are as a rule indistinguishable clinically.

B. Laboratory Findings:

In most cases of bacterial conjunctivitis, the organisms can be identified by the microscopic examination of conjunctival scrapings stained with Gram's stain or Giemsa's stain; this reveals numerous polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Conjunctival scrapings for microscopic examination and culture are recommended for all cases and are mandatory if the disease is purulent, membranous, or pseudomembranous. Antibiotic sensitivity studies are also desirable, but empirical antibiotic therapy should be started. When the results of antibiotic sensitivity tests become available, specific antibiotic therapy can then be instituted.

Complications & Sequelae

Chronic marginal blepharitis often accompanies staphylococcal conjunctivitis except in very young patients who are not subject to blepharitis. Conjunctival scarring may follow both pseudomembranous and membranous conjunctivitis, and in rare cases corneal ulceration and perforation supervene.

Marginal corneal ulceration may follow infection with N gonorrhoeae, N kochii, N meningitidis, H aegyptius, S aureus, and M catarrhalis; if the toxic products of N gonorrhoeae diffuse through the cornea into the anterior chamber, they may cause toxic iritis.

Treatment

Specific therapy of bacterial conjunctivitis depends on identification of the microbiologic agent. While waiting for laboratory reports, the physician can start topical therapy with an antimicrobial drug. In any purulent conjunctivitis in which Gram's stain shows gram-negative diplococci suggestive of Neisseria, both system and topical therapy should be started immediately. If there is no corneal involvement, a single intramuscular dose of ceftriaxone, 1 g, is usually adequate systemic therapy. If there is corneal involvement, a 5-day course of parenteral ceftriaxone, 1-2 g daily, is required.

In acute purulent and mucopurulent conjunctivitis, the conjunctival sac should be irrigated with saline solution as necessary to remove the conjunctival secretions. To prevent spread of the disease, the patient and family should be instructed to give special attention to personal hygiene.

Course & Prognosis

Acute bacterial conjunctivitis is almost always self-limited. Untreated, it may last 10-14 days; if properly treated, 1-3 days. The exceptions are staphylococcal conjunctivitis (which may progress to blepharoconjunctivitis and enter a chronic phase) and gonococcal conjunctivitis (which when untreated can lead to corneal perforation and endophthalmitis). Since the conjunctiva may be the portal of entry for the meningococcus to the bloodstream and meninges, septicemia and meningitis may be the end results of meningococcal conjunctivitis.

Chronic bacterial conjunctivitis may not be self-limited and may become a troublesome therapeutic problem.

CHLAMYDIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

1. TRACHOMA

Trachoma is one of the most ancient of known diseases. It was recognized as a cause of trichiasis as early as the 27th century BC and affects all races. With 300-600 million of the world's population afflicted, it is one of the most common of all chronic diseases. Its regional variations in prevalence and severity can be explained on the basis of variations in the personal hygiene and standards of living of the world's peoples, the climatic conditions under which they live, the prevailing age at onset, and the frequency and type of the prevailing concomitant bacterial eye infections. Blinding trachoma occurs in many parts of Africa, some parts of Asia, among Australian aborigines, and in northern Brazil. Communities with milder nonblinding trachoma occur in the same regions and in some areas of Latin America and the Pacific Islands.

Trachoma is usually bilateral. It is spread by direct contact or fomites, usually from other family members (siblings, parents), who should also be examined for the disease. Insect vectors, especially flies and gnats, may play a role in transmission. The acute forms of the disease are more infectious than the cicatricial forms, and the larger the inoculum the more severe the disease. Spread is often associated with epidemics of bacterial conjunctivitis and with the dry seasons in tropical and semitropical countries.

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs:

Trachoma is initially a chronic follicular conjunctivitis of childhood that progresses to conjunctival scarring. In severe cases, inturned eyelashes occur in early adult life as a result of severe conjunctival scarring. The constant abrasion of inturned lashes and a defective tear film lead to corneal scarring, usually after the age of 50 years.

The incubation period of trachoma averages 7 days but varies from 5 to 14 days. In an infant or child, the onset is usually insidious, and the disease may resolve with minimal or no complications. In adults, the onset is often subacute or acute, and complications may develop early. At onset, trachoma often resembles other bacterial conjunctivitis, the signs and symptoms usually consisting of tearing, photophobia, pain, exudation, edema of the eyelids, chemosis of the bulbar conjunctiva, hyperemia, papillary hypertrophy, tarsal and limbal follicles, superior keratitis, pannus formation, and a small, tender preauricular node.

In established trachoma, there may also be superior epithelial keratitis, subepithelial keratitis, pannus, superior limbal follicles, and ultimately the pathognomonic cicatricial remains of these follicles, known as Herbert's pits-small depressions in the connective tissue at the limbocorneal junction covered by epithelium. The associated pannus is a fibrovascular membrane arising from the limbus, with vascular loops extending onto the cornea. All of the signs of trachoma are more severe in the upper than in the lower conjunctiva and cornea.

To establish the presence of endemic trachoma in a family or community, a substantial number of children must have at least two of the following signs:

Five or more follicles on the flat tarsal conjunctiva lining the upper eye lid.

Typical conjunctival scarring of the upper tarsal conjunctiva.

Limbal follicles or their sequelae (Herbert's pits).

An even extension of blood vessels onto the cornea, most marked at the upper limbus.

While occasional individuals will meet these criteria, it is the wide distribution of these signs in individual families and in a community that identify the presence of trachoma.

For control purposes, the World Health Organization has developed a simplified method to describe the disease. This includes the following signs:

| UNDEFINED: SIDEBARCONTENT | ||||

The presence of TF and TI indicates active infectious trachoma and a need for treatment. TS is evidence of damage from the disease. TT is potentially blinding and is an indication for corrective lid surgery. CO is the final blinding lesion of trachoma.

B. Laboratory Findings:

Chlamydial inclusions can be found in Giemsa-stained conjunctival scrapings, but they are not always present. Inclusions appear in the Giemsa-stained preparations as particulate, dark purple or blue cytoplasmic masses that cap the nucleus of the epithelial cell. Fluorescent antibody stains and enzyme immunoassay tests are available commercially and are widely used in clinical laboratories. These new tests have superseded Giemsa staining of conjunctival smears and isolation of chlamydial agent in cell culture.

The agent of trachoma resembles the agent of inclusion conjunctivitis morphologically, but the two can be differentiated serologically by microimmunofluorescence. Trachoma is caused by Chlamydia trachomatis serotypes A, B, Ba, or C.

Differential Diagnosis

Epidemiologic and clinical factors to be considered in differentiating trachoma from other forms of follicular conjunctivitis can be summarized as follows:

No history of exposure to endemic trachoma speaks against the diagnosis.

Viral follicular conjunctivitis (due to infection with adenovirus, herpes simplex virus, picornavirus, and coxsackievirus) usually has an acute onset and is clearly resolving by 2-3 weeks.

Infection with genitally transmitted chlamydial strains usually has an acute onset in sexually active individuals.

Chronic follicular conjunctivitis with exogenous substances (molluscum nodules of the lids, topical eye medications) resolve slowly when the nodules are removed or the drug withdrawn.

Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome is manifested by massively enlarged preauricular or cervical lymph nodes, though the conjunctival lesion may be follicular.

Young children often have some follicles (like hypertrophied tonsils), a condition known as folliculosis.

The atopic conditions vernal conjunctivitis and atopic keratoconjunctivitis are associated with giant papillae that are elevated and often polygonal, with a milky-red appearance. Eosinophils are present in smears.

Look for a history of contact lens intolerance in patients with conjunctival scarring and pannus; giant papillae in some contact lens wearers can be confused with trachoma follicles.

Complications & Sequelae

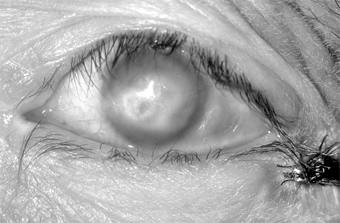

Conjunctival scarring is a frequent complication of trachoma and can destroy the ductules of the accessory lacrimal glands and obliterate the orifices of the lacrimal gland. These effects may drastically reduce the aqueous component of the precorneal tear film, and the film's mucous components may be reduced by loss of goblet cells. The scars may also cause distortion of the upper lid with inward deviation of individual lashes (trichiasis) or of the whole lid margin (entropion), so that the lashes constantly abrade the cornea. This often leads to corneal ulceration, bacterial corneal infections, and corneal scarring (Figure 5-2).

Figure 5-2: Advanced trachoma following corneal ulceration and scarring. Note the fly on the temporal aspect of the lower lid. The fly is a principal vector for trachoma.

Ptosis, nasolacrimal duct obstruction, and dacryocystitis are other common complications of trachoma.

Treatment

Striking clinical improvement can usually be achieved with tetracycline, 1-1.5 g/d orally in four divided doses for 3-4 weeks; doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily for 3 weeks; or erythromycin, 1 g/d orally in four divided doses for 3-4 weeks. Several courses are sometimes necessary for actual cure. Systemic tetracyclines should not be given to a child under 7 years of age or to a pregnant woman, since tetracycline binds to calcium in the developing teeth and in the growing bone and may lead to congenital yellowish discoloration of the permanent teeth and skeletal (eg, clavicular) abnormalities.

Topical ointments or drops, including preparations of sulfonamides, tetracyclines, erythromycin, and rifampin, used four times daily for 6 weeks, are equally effective.

From the time therapy is begun, its maximum effect is usually not achieved for 10-12 weeks. The persistence of follicles on the upper tarsus for some weeks after a course of therapy should therefore not be construed as evidence of therapeutic failure.

Surgical correction of inturned eyelashes is essential to prevent scarring from late trachoma in developing countries. Such surgery is sometimes done by nonspecialist physicians or specially trained auxiliary personnel.

Course & Prognosis

Characteristically, trachoma is a chronic disease of long duration. Under good hygienic conditions (specifically, face-washing of young children), the disease resolves or becomes milder so that severe sequelae are avoided. About 6-9 million people in the world today have major visual loss from trachoma.

2. INCLUSION CONJUNCTIVITIS

Inclusion conjunctivitis is often bilateral and usually occurs in sexually active young people. The chlamydial agent infects the urethra of the male and the cervix of the female. Transmission to the eyes of adults is usually by oral-genital sexual practices or hand to eye transmission. About one in 300 persons with genital chlamydial infection develops the eye disease. Indirect transmission has been reported to occur in inadequately chlorinated swimming pools. In newborns, the agent is transmitted during birth by direct contamination of the conjunctiva with cervical secretions. Credé prophylaxis gives only partial protection against inclusion conjunctivitis.

Clinical Findings

A. Symptoms and Signs:

Inclusion conjunctivitis may have an acute or a subacute onset. The patient frequently complains of redness of the eyes, pseudoptosis, and discharge, especially in the mornings. Newborns have papillary conjunctivitis and a moderate amount of exudate, and in hyperacute cases pseudomembranes occasionally form and can lead to scarring. Since the newborn has no adenoid tissue in the stroma of the conjunctiva, there is no follicle formation; but if the conjunctivitis persists for 2-3 months, follicles appear and the conjunctival picture is like that in older children and adults. In the newborn, chlamydial infection may cause pharyngitis, otitis media, and interstitial pneumonitis.

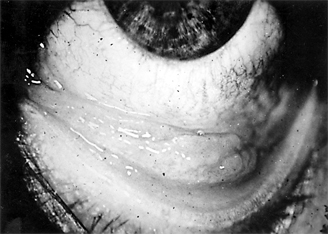

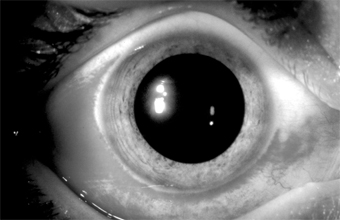

In adults, the conjunctiva of both tarsi-especially the lower tarsus-have papillae and follicles (Figure 5-3). Since pseudomembranes do not usually form in the adult, scarring does not usually occur. Superficial keratitis may be noted superiorly and, less often, a small superior micropannus (< 1-2 mm). Subepithelial opacities, usually marginal, often develop. Otitis media may occur as a result of infection of the auditory tube.

Figure 5-3: Acute follicular conjunctivitis caused by inclusion conjunctivitis in a 22-year-old man with urethritis. (Courtesy of K Tabbara.)

B. Laboratory Findings:

The same tests should be performed as for trachoma (above). In neonatal chlamydial ophthalmia, Giemsa-stained smears often have many inclusions. Inclusion conjunctivitis is caused by C trachomatis serotypes D-K with occasional isolations of serotype B. Serologic determinations are not useful in the diagnosis of ocular infections, but measurement of IgM antibody levels is extremely valuable in the diagnosis of chlamydial pneumonitis in infants.

Differential Diagnosis

Inclusion conjunctivitis can be clinically differentiated from trachoma on the following grounds:

Active, follicular trachoma occurs commonly in young children or others living in or exposed to a community with endemic trachoma; inclusion conjunctivitis occurs in sexually active adolescents or adults.

Conjunctival scarring is very rare in adult inclusion conjunctivitis.

Herbert's pits are a unique sign that trachoma was present at some time in the past.

Treatment

A. In Infants:

Give oral erythromycin suspension, 40 mg/kg/d in four divided doses for at least 14 days. Oral medication is necessary because chlamydial infection also involves the respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts. Topical antibiotics (tetracyclines, erythromycin, sulfonamides) are not useful in newborns treated with oral erythromycin. Both parents should be treated with oral tetracyclines or erythromycin for their genital tract infection.

B. In Adults:

Cure can be achieved with a 3-week course of oral tetracycline, 1-1.5 g/d; doxycycline, 100 mg orally twice daily; or erythromycin, 1 g/d. (Systemic tetracyclines should not be given to a pregnant woman or a child under 7 years of age, since they cause epiphysial problems in the fetus or staining of the young child's teeth.) The patient's sexual partners should be examined and treated.

When one of the standard therapeutic regimens is followed, recurrences are rare. If untreated, inclusion conjunctivitis runs a course of 3-9 months or longer. The average duration is 5 months.

3. CONJUNCTIVITIS CAUSED BY OTHER CHLAMYDIAL AGENTS

Lymphogranuloma venereum conjunctivitis is a rare sexually transmitted disease. Lymphogranuloma venereum causes a dramatic granulomatous conjunctival reaction with greatly enlarged preauricular nodes (Parinaud's syndrome). It is caused by C trachomatis serotypes L1, L2 or L3.

Chlamydia psittaci only rarely causes conjunctivitis in humans. Strains from parrots (psittacosis) and cats (feline pneumonitis) have caused follicular conjunctivitis in humans. The prototype strains of Chlamydia pneumoniae were isolated from the conjunctiva but have not been identified as a cause of eye disease.

VIRAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Viral conjunctivitis, a common affliction, can be caused by a wide variety of viruses. Severity ranges from severe, disabling disease to mild, rapidly self-limited infection.

1. ACUTE VIRAL FOLLICULAR CONJUNCTIVITIS

Pharyngoconjunctival Fever

Pharyngoconjunctival fever is characterized by fever of 38.3-40 °C (101-104 °F), sore throat, and a follicular conjunctivitis in one or both eyes. The follicles are often very prominent on both the conjunctiva (Figure 5-4) and the pharyngeal mucosa. The disease can be either bilateral or unilateral. Injection and tearing often occur, and there may be transient superficial epithelial keratitis and occasionally some subepithelial opacities. Preauricular lymphadenopathy (nontender) is characteristic. The syndrome may be incomplete, consisting of only one or two of the cardinal signs (fever, pharyngitis, and conjunctivitis).

Figure 5-4: Acute follicular conjunctivitis due to adenovirus type 3. (Courtesy of P Thygeson.)

Pharyngoconjunctival fever is caused regularly by adenovirus type 3 and occasionally by types 4 and 7. The virus can be grown on HeLa cells and identified by neutralization tests. As the disease progresses, it can also be diagnosed serologically by a rising titer of neutralizing antibody to the virus. Clinical diagnosis is a simple matter, however, and clearly more practical.

Conjunctival scrapings contain predominantly mononuclear cells, and no bacteria grow in cultures. The condition is more common in children than in adults and can be transmitted poorly in chlorinated swimming pools. There is no specific treatment, but the conjunctivitis is self-limited, usually lasting about 10 days.

Epidemic Keratoconjunctivitis

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is usually bilateral. The onset is often in one eye only, however, and as a rule the first eye is more severely affected. At onset the patient notes injection, moderate pain, and tearing, followed in 5-14 days by photophobia, epithelial keratitis, and round subepithelial opacities. Corneal sensation is normal. A tender preauricular node is characteristic. Edema of the eyelids, chemosis, and conjunctival hyperemia mark the acute phase, with follicles and subconjunctival hemorrhages often appearing within 48 hours. Pseudomembranes (and occasionally true membranes) may occur and may be followed by flat scars or symblepharon formation (Figure 5-5).

Figure 5-5: Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis. Thick white membrane of upper palpebral conjunctiva.

The conjunctivitis lasts for 3-4 weeks at most. The subepithelial opacities are concentrated in the central cornea, usually sparing the periphery, and may persist for months but heal without scars.

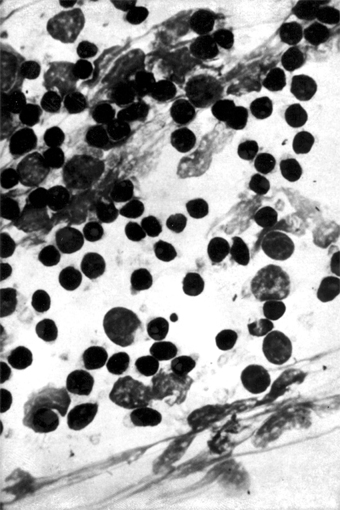

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis is caused by adenovirus types 8, 19, 29, and 37 (subgroup D of the human adenoviruses). They can be isolated in cell culture and identified by neutralization tests. Scrapings from the conjunctiva show a primarily mononuclear inflammatory reaction (Figure 5-6); when pseudomembranes occur, neutrophils may also be prominent.

Figure 5-6: Mononuclear cell reaction in conjunctival scrapings of a patient with viral conjunctivitis caused by adenovirus type 8. (Courtesy of M Okumoto.)

Epidemic keratoconjunctivitis in adults is confined to the external eye, but in children there may be such systemic symptoms of viral infection as fever, sore throat, otitis media, and diarrhea. Nosocomial transmission during eye examinations takes place all too often by way of the physician's fingers, use of improperly sterilized ophthalmic instruments, or use of contaminated solutions. Eye solutions, particularly topical anesthetics, can be contaminated when a dropper tip aspirates infected material from the conjunctiva or cilia. The virus can persist in the solution, which becomes a source of spread.

The danger of contaminated solution bottles can be avoided by the use of individual sterile droppers or unit-dose packages of eye drops. Regular hand washing between examinations and careful cleaning and sterilization of instruments that touch the eyes-especially tonometers-are also mandatory. Applanation tonometers should be cleaned by wiping with alcohol or hypochlorite, then rinsing with sterile water and carefully drying.

There is no specific therapy at present, but cold compresses will relieve some symptoms. Corticosteroids during acute conjunctivitis may prolong the late corneal involvement and so should be avoided. Antibacterial agents should be given if bacterial superinfection occurs.

Herpes Simplex Virus Conjunctivitis

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) conjunctivitis, usually a disease of young children, is an uncommon entity characterized by unilateral injection, irritation, mucoid discharge, pain, and mild photophobia. It occurs during primary infection with HSV or during recurrent episodes of ocular herpes (Figure 5-7). It is often associated with herpes simplex keratitis, in which the cornea shows discrete epithelial lesions that usually coalesce to form single or multiple branching epithelial (dendritic) ulcers. The conjunctivitis is follicular or, less often, pseudomembranous. (Patients receiving topical antivirals may develop follicular conjunctivitis that can be differentiated because the herpetic follicular conjunctivitis has an acute onset.) Herpetic vesicles may sometimes appear on the eyelids and lid margins, associated with severe edema of the eyelids. Typically, there is a small tender preauricular node.

Figure 5-7: Primary ocular herpes. (Courtesy of HB Ostler.)

No bacteria are found in scrapings or recovered in cultures. If the conjunctivitis is follicular, the predominant inflammatory reaction is mononuclear, but if it is pseudomembranous the predominant reaction is polymorphonuclear owing to the chemotaxis of necrosis. Intranuclear inclusions (because of the margination of the chromatin) can be seen in conjunctival and corneal cells if Bouin fixation and the Papanicolaou stain are used but not in Giemsa-stained smears. The finding of multinucleated giant epithelial cells has diagnostic value.

The virus can be readily isolated by gently rubbing a dry cotton-tipped applicator over the conjunctiva and transferring the infected cells to a susceptible tissue culture.

HSV conjunctivitis may persist for 2-3 weeks, and if it is pseudomembranous it may leave fine linear or flat scars. Complications consist of corneal involvement (including dendrites) and vesicles on the skin. Although type 1 herpesvirus causes the overwhelming majority of ocular cases, type 2 is the usual cause in newborns and a rare cause in adults. In the newborn, there may be generalized disease with encephalitis, chorioretinitis, hepatitis, etc. Any HSV infection in the newborn must be treated with systemic antiviral therapy (acyclovir) and monitored in a hospital setting.

If the conjunctivitis occurs in a child over 1 year of age or in an adult, it is usually self-limited and may not require therapy. Topical or systemic antivirals should be given, however, to prevent corneal involvement. For corneal ulcers, corneal debridement may be performed by gently wiping the ulcer with a dry cotton swab, applying antiviral drops, and patching the eye for 24 hours. Topical antivirals alone should be applied for 7-10 days: trifluridine every 2 hours while awake, or vidarabine ointment five times a day, or idoxuridine 0.1%, 1 drop every hour while awake and 1 drop every 2 hours during the night. Herpetic keratitis may also be treated with 3% acyclovir ointment (not available in the USA) five times daily for 10 days or with oral acyclovir, 400 mg five times a day for 7 days. The use of steroids is contraindicated, since they may aggravate herpes simplex infections and convert the disease from a short, self-limited process to a severe, greatly prolonged one.

Newcastle Disease Conjunctivitis

Newcastle disease conjunctivitis is a rare disorder characterized by burning, itching, pain, redness, tearing, and (rarely) blurring of vision. It often occurs in small epidemics among poultry workers handling infected birds or among veterinarians or laboratory helpers working with live vaccines or virus.

The conjunctivitis resembles that caused by other viral agents, with chemosis, a small preauricular node, and follicles on the upper and lower tarsus. No treatment is available or necessary for this self-limited disease.

Acute Hemorrhagic Conjunctivitis

All of the continents and most of the islands of the world have had major epidemics of acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis. It was first recognized in Ghana in 1969. It is caused by enterovirus type 70 and occasionally by coxsackievirus A24.

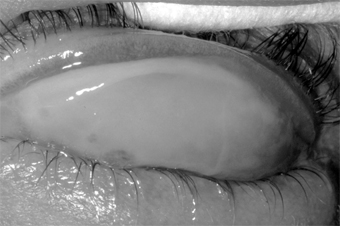

Characteristically, the disease has a short incubation period (8-48 hours) and course (5-7 days). The usual signs and symptoms are pain, photophobia, foreign body sensation, copious tearing, redness, lid edema, and subconjunctival hemorrhages (Figure 5-8). Chemosis sometimes also occurs. The subconjunctival hemorrhages are usually diffuse but may be punctate at onset, beginning in the upper bulbar conjunctiva and spreading to the lower. Most patients have preauricular lymphadenopathy, conjunctival follicles, and epithelial keratitis. Anterior uveitis has been reported; fever, malaise, and generalized myalgia have been observed in 25% of cases; and motor paralysis of the lower extremities has occurred in rare cases in India and Japan.

Figure 5-8: Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis.

The virus is transmitted by close person-to-person contact and by such fomites as common linens, contaminated optical instruments, and water. Recovery occurs within 5-7 days, and there is no known treatment. In the USA, closing of schools has been done to stop epidemics.

2. CHRONIC VIRAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Molluscum Contagiosum Blepharoconjunctivitis

A molluscum nodule on the lid margins or the skin of the lids or brow may produce unilateral chronic follicular conjunctivitis, superior keratitis, and superior pannus and may resemble trachoma. The inflammatory reaction is predominantly mononuclear (unlike the reaction in trachoma), and the round, waxy, pearly-white, noninflammatory lesion with an umbilicated center is typical of molluscum contagiosum (Figure 5-9). Biopsy shows eosinophilic cytoplasmic inclusions that fill the entire cytoplasm of the enlarged cell, pushing its nucleus to one side.

Figure 5-9: Molluscum contagiosum of lid margin. Follicular conjunctivitis was present.

Excision, simple incision of the nodule to allow peripheral blood to permeate it, or cryotherapy cures the conjunctivitis. On very rare occasions (reports of only two cases have appeared in the literature), molluscum nodules have occurred on the conjunctiva. In these cases, excision of the nodule has also relieved the conjunctivitis. Multiple lid or facial lesions of molluscum contagiosum have been seen in patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS).

Varicella-Zoster Blepharoconjunctivitis

Hyperemia and an infiltrative conjunctivitis-associated with the typical vesicular eruption along the dermatomal distribution of the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve-are characteristic of herpes zoster (preferably called simply zoster). The conjunctivitis is usually papillary, but follicles, pseudomembranes, and transitory vesicles that later ulcerate have all been noted. A tender preauricular lymph node occurs early in the disease. Scarring of the lid, entropion, and the misdirection of individual lashes are sequelae.

The lid lesions of varicella, which are like the skin lesions (pox) elsewhere, may appear on both the lid margins and the lids and often leave scars. A mild exudative conjunctivitis often occurs, but discrete conjunctival lesions (except at the limbus) are very rare. Limbal lesions resemble phlyctenules and may go through all the stages of vesicle, papule, and ulcer. The adjacent cornea becomes infiltrated and may vascularize.

In both zoster and varicella, scrapings from lid vesicles contain giant cells and a predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes; scrapings from the conjunctiva in varicella and from conjunctival vesicles in zoster may contain giant cells and monocytes. The virus can be recovered in tissue cultures of human embryo cells.

Oral acyclovir in high doses (800 mg orally five times daily for 10 days), if given early in the course of the disease, appears to limit the severity of the illness.

Measles Keratoconjunctivitis

The characteristic enanthem of measles frequently precedes the skin eruption. At this early stage, the conjunctiva may have a peculiar glassy appearance, followed within a few days by swelling of the semilunar fold (Meyer's sign). Several days before the skin eruption, an exudative conjunctivitis with a mucopurulent discharge develops, and at the time of the skin eruption, Koplik's spots appear on the conjunctiva and occasionally on the caruncle. At some time (early in children, late in adults), epithelial keratitis supervenes.

In the immunocompetent patient, measles keratoconjunctivitis has few or no sequelae, but in malnourished or otherwise immunoincompetent patients the ocular disease is frequently associated with a secondary HSV or bacterial infection due to S pneumoniae, H influenzae, and other organisms. These agents may lead to purulent conjunctivitis with associated corneal ulceration and severe visual loss. Herpes infection can cause severe corneal ulceration with corneal perforation and loss of vision in poorly nourished children in developing countries.

Conjunctival scrapings show a mononuclear cell reaction unless there are pseudomembranes or secondary infection. Giemsa-stained preparations contain giant cells. Since there is no specific therapy, only supportive measures are indicated unless there is secondary infection.

RICKETTSIAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

All rickettsiae recognized as pathogenic for humans may attack the conjunctiva, and the conjunctiva may be their portal of entry.

Q fever is associated with severe conjunctival hyperemia. Treatment with systemic tetracycline or chloramphenicol is curative.

Marseilles fever (boutonneuse fever) is often associated with ulcerative or granulomatous conjunctivitis and a grossly visible preauricular lymph node.

Endemic (murine) typhus, scrub typhus, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, and epidemic typhus have associated, variable, and usually mild conjunctival signs.

FUNGAL CONJUNCTIVITIS

Candidal Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis caused by Candida species (usually Candida albicans) is a rare infection that usually appears as a white plaque. This may occur in diabetics or immunocompromised patients as an ulcerative or granulomatous conjunctivitis.

Scrapings show a polymorphonuclear cell inflammatory reaction. The organism grows readily on blood agar or Sabouraud's medium and can be readily identified as a budding yeast or, rarely, as pseudohyphae.

The infection responds to amphotericin B (3-8 mg/mL) in aqueous (not saline) solution or to applications of nystatin dermatologic cream (100,000 units/g) four to six times daily. The ointment must be applied carefully to be sure that it reaches the conjunctival sac and does not just build up on the lid margins.

Other Fungal Conjunctivitides

Sporothrix schenckii may rarely involve the conjunctiva or the eyelids. It is a granulomatous disease associated with a visible preauricular node. Microscopic examination of a biopsy of the granuloma reveals gram-positive, cigar-shaped conidia (spores).

Rhinosporidium seeberi may rarely affect the conjunctiva, lacrimal sac, lids, canaliculi, and sclera. The typical lesion is a polypoid granuloma that bleeds after minimal trauma. Histologic examination shows a granuloma with enclosed large spherules containing myriads of endospores. Treatment is by simple excision and cauterization of the base.

Coccidioides immitis may rarely cause a granulomatous conjunctivitis associated with a grossly visible preauricular node (Parinaud's oculoglandular syndrome). This is not a primary disease but a manifestation of metastatic infection from a primary pulmonary infection (San Joaquin Valley fever). Disseminated disease suggests a poor prognosis.

PARASITIC CONJUNCTIVITIS*

Thelazia californiensis Infection

The natural habitat of this roundworm is the eye of the dog, but it can also infect the eyes of cats, sheep, black bears, horses, and deer. Accidental infection of the human conjunctival sac has occurred. The disease can be treated effectively by removing the worms from the conjunctival sac with forceps or a cotton-tipped applicator.

Loa loa Infection

L loa is the eye worm of Africa. It lives in the connective tissue of humans and monkeys, and the monkey may be its reservoir. The parasite is transmitted by the bite of the horse or mango fly. The mature worm may then migrate to the lid, the conjunctiva, or the orbit.

Infection with L loa is accompanied by a 60-80% eosinophilia, but diagnosis is made by identifying the worm on removal or by finding microfilariae in blood examined at midday.

Diethylcarbamazine is currently the drug of choice. Ivermectin is being evaluated.

Ascaris lumbricoides Infection (Butcher's Conjunctivitis)

Ascaris may cause a rare type of violent conjunctivitis. When butchers or persons performing postmortem examinations cut tissue containing Ascaris, the tissue juice of some of the organisms may hit them in the eye. This can be followed by a violent and painful toxic conjunctivitis marked by extreme chemosis and lid edema. Treatment consists of rapid and thorough irrigation of the conjunctival sac.

Trichinella spiralis Infection

This parasite does not cause a true conjunctivitis, but in the course of its general dissemination there may be a doughy edema of the upper and lower eyelids, and over 50% of patients have chemosis-a pale, lemon-yellow swelling most marked over the lateral and medial rectus muscles and fading toward the limbus. The chemosis may last a week or more, and there is often pain on movement of the eyes.

Schistosoma haematobium Infection

Schistosomiasis (bilharziasis) is endemic in Egypt, especially in the region irrigated by the Nile. Granulomatous conjunctival lesions appearing as small, soft, smooth, pinkish-yellow tumors occur, especially in males. The symptoms are minimal. Diagnosis depends on microscopic examination of biopsy material, which shows a granuloma containing lymphocytes, plasma cells, giant cells, and eosinophils surrounding bilharzial ova in various stages of disintegration.

Treatment consists of excision of the conjunctival granuloma and systemic therapy with antimonials such as niridazole.

Taenia solium Infection

This parasite rarely causes conjunctivitis but more often invades the retina, choroid, or vitreous to produce ocular cysticercosis. As a rule, the affected conjunctiva shows a subconjunctival cyst in the form of a localized hemispherical swelling, usually at the inner angle of the lower fornix, which is adherent to the underlying sclera and painful on pressure. The conjunctiva and lid may be inflamed and edematous.

Diagnosis is based on a positive complement fixation or precipitin test or on demonstration of the organism in the gastrointestinal tract. Eosinophilia is a constant feature.

The best treatment is to excise the lesion. The intestinal condition can be treated by niclosamide.

Pthirus pubis Infection (Pubic Louse Infection)

P pubis may infest the cilia and margins of the eyelids. Because of its size, the pubic louse seems to require widely spaced hair. For this reason it has a predilection for the widely spaced cilia as well as for pubic hair. The parasites apparently release an irritating substance (probably feces) that produces a toxic follicular conjunctivitis in children and an irritating papillary conjunctivitis in adults. The lid margin is usually red, and the patient may complain of intense itching.

Finding the adult organism or the ova-shaped nits cemented to the eyelashes is diagnostic.

Lindane (Kwell) 1% or RID (pyrethrins), applied to the pubic area and lash margins after removal of the nits, is usually curative. Application of lindane or RID to the lid margins must be undertaken with great care to avoid contact with the eye. Any ointment applied to the lid margin tends to smother the adult organisms. The patient's family and close contacts should be examined and treated. All clothes and fomites should be washed.

Ophthalmomyiasis

Myiasis is infection with larvae of flies. Many different species of flies may produce myiasis. The ocular tissues may be injured by mechanical transmission of disease-producing organisms and by the parasitic activities of the larvae in the ocular tissues. The larvae are able to invade either necrotic or healthy tissue. Many become infected by accidental ingestion of the eggs or larvae or by contamination of external wounds or skin. Infants and young children, alcoholics, and debilitated unattended patients are common targets for infection with myiasis-producing flies.

These larvae may affect the ocular surface, the intraocular tissues, or the deeper orbital tissues.

Ocular surface involvement may be caused by Musca domestica, the housefly, Fannia, the latrine fly, and Oestrus ovis, the sheep botfly. These flies deposit their eggs at the lower lid margin or inner canthus, and the larvae may remain on the surface of the eye, causing irritation, pain, and conjunctival hyperemia.

Treatment of ocular surface myiasis is by mechanical removal of the larvae after topical anesthesia.

** Onchocerciasis is discussed in Chapter 7

PREVIOUS | NEXT

Page: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14

10.1036/1535-8860.ch5