The preoperative assessment should ideally cover three broad areas: (1) detection of any acute or chronic medical problems; (2) acquisition of enough medical information about the infant or child to assure that the child is in optimal health; and (3) identification of any risk factors in the medical or family history that might unexpectedly interfere with a good outcome. In this process, a pertinent medical and family history is taken, hospital and office clinical records are reviewed, a careful physical examination is performed, and the decision to obtain any laboratory studies is made.

The examination should precede and not replace consultation with the anesthesiologist. It should provide the anesthesiologist with enough information to determine the child's baseline health status and to target any ways in which the patient deviates from the norm and may require special attention or monitoring. The pediatrician should highlight for the anesthesiologist any concerns that may compromise the safe delivery of anesthesia or influence the patient's recovery.

In addition to providing the medical preparation, the pediatrician who has known the child and parents for a while and is a trusted friend can be very helpful in .allaying anxiety. By recognizing the normal concerns and feelings about any hospitalization or surgery, he or she can allow time for discussion of these issues during the examination before surgery. Parents should be reassured that the morbidity rate for elective ophthalmic surgery in a major medical center is very low.1 The pediatrician may also provide answers to questions in frank and simple terms, thus decreasing the fears that even a minor procedure may generate.

Same-day surgery minimizes the psychological impact of the hospitalization on the child, is convenient, and is cost effective.2 However, a discussion of the possibility of a lengthier hospital stay for the more medically-at-risk child must be introduced at this time if indicated. The hospital experience is routine for the physician but hardly a benign event for the child and the family.3 The pediatrician, the surgeon, and the anesthesiologist need to work together and communicate their findings and intentions clearly. This will result in the best outcome for their mutual patient.

THE MEDICAL HISTORY

While taking the medical history, the pediatrician uncovers information about the child's general health and any symptoms that may require a more detailed preoperative medical evaluation. History-taking is one of the best screens for disease.4

Specific questions should be asked about any recent symptoms of illness, fever, rashes, or recent exposures to infectious diseases. Exposure to chicken pox within the last three weeks, exposure to a streptococcal throat infection within the last 3 to 5 days, and a history of family members ill at home are significant.

Cardiac and pulmonary signs and symptoms in the child are specifically sought, including cold or cough, chest pain, wheezing, asthma or allergies, history of recent or recurrent pneumonia or bronchitis, shortness of breath, pallor, duskiness, or fatigue with exertion.5 The medical history should also determine exposure to cigarette smoke in the home as well as the possibility of lead or other toxin exposure.

Information should be obtained on neurologic status, level of cognitive function, behavior, presence of seizures (type and treatment), complaints of pain, or headaches. The extent of chronic conditions of the nervous system such as mental retardation or cerebral palsy and the presence of sensory impairment such as deafness or visual deficits should be documented.

Inquire about easy bruising, bleeding from gums, bleeding in the past during minor surgery, bleeding into deep tissue or joints, or a history of aspirin ingestion.

Nutritional history includes dietary intake, special diet or restrictions, recent weight loss or excessive weight gain, and the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms.

Recent events in the child's life that may produce stress are explored: school demands, the birth of a sibling, illness of a parent (especially the primary caregiver), divorce, separation, or a move. Attention to psychological issues helps to determine if the child is more emotionally vulnerable than usual or if the timing of the elective procedure should be changed.2

In addition to the routine questions of drug history, ask if the child is subject to motion sickness. Some references report that nearly all children subjected to motion sickness will have postoperative vomiting and recommend prophylactic treatment.1 A drug history of eye drop use is important, because phospholine iodide inhibits pseudocholinesterase and may prolong the action of succinyl choline.1

Healthy multihandicapped children frequently require ophthalmic surgery and a detailed past medical history is needed. Strabismus often occurs in patients with congenital infections, central nervous system (CNS) trauma or disease, previous craniotomy for removal of a brain tumor, history of meningitis, severe prematurity, and respiratory distress syndrome. These children require a full review of their medical history, including hospitalizations and previous surgeries, for a complete understanding of the factors contributing to the child's well-being during anesthesia and surgery.

FAMILY HISTORY

The family history should include questions about parents' and siblings' health as well as the incidence of hereditary disease, congenital anomalies, allergies and asthma, blood dyscrasias or bleeding disorders, and the response of family members to general anesthesia. The pediatrician must inquire if any family member had a problem during or after anesthesia and surgery. There is an association between strabismus and blepharoptosis and malignant hyperthermia (hyperpyrexia). Although rare, it should be asked about.

THE PHYSICAL EXAMINATION

This examination should be done one week or less prior to inpatient surgery and one month or less prior to outpatient surgery.6 This evaluation should answer the question, “Is this child healthy and able to tolerate anesthesia and surgery?”

A complete physical examination begins with a general observation of the child in which body proportions, nutritional status, behavior, and interaction with parents are noted.

Vital signs in the normal range indicate a stable physical condition. A fever, temperature 101°F (38.4°C) or higher, is an indication to cancel elective surgery. Irregular pulse, abnormal blood pressure, tachypnea, or noisy respirations should alert the physician to investigate a potential problem.

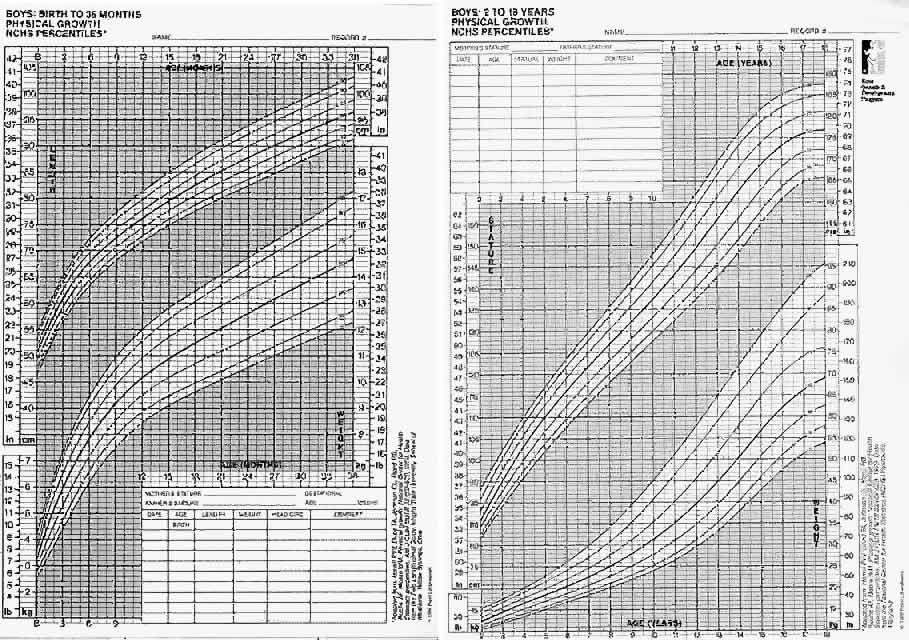

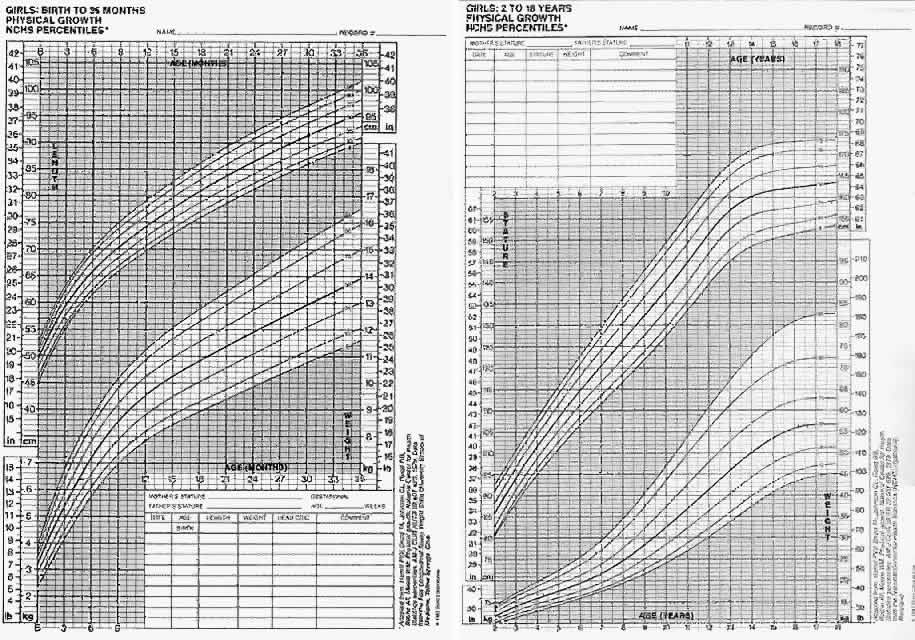

Measurements of height, weight, and head size are recorded and compared to established norms to assess growth, development, and nutrition (Figs. 1 AND 2).

It is very important to inspect the head and neck structures very carefully for conditions that would make intubation difficult or contribute to upper airway obstruction after sedation or induction. Because of their small size, children's airways can be easily compromised.7 Young infants are obligate nose breathers and a “stuffy nose” is a significant problem. Other sources for potential problems include small nares, narrow palate, posterior pharyngeal secretions, ear infections on otoscopic exam, large tongue, loose teeth, hypertrophied tonsils, small underdeveloped mandible, and any limitation of movement of the neck. Symptoms referable to ligamentous laxity with instability of the atlantoaxial joint of the cervical spine in Down syndrome patients is discussed in a section to follow. Patients who have a head tilt associated with a cyclovertical muscle palsy should not have an increased risk for an airway management problem.1

Emphasis is placed on the heart and lungs with a careful cardiopulmonary examination. If a heart murmur, tales in the chest, coughing, or wheezing are present, a more complete evaluation is warranted. Cardiovascular assessment includes examination of the skin and the nail beds and assessment of skin perfusion and temperature, especially in the limbs.7

Examination of the abdomen for presence of distention, increased organ size, or the presence of a mass should also be included. In children with cerebral palsy, a rectal examination should be performed. It is advisable to relieve constipation prior to surgery, as anesthesia could worsen this condition.

The child is observed for neurologic deficits or a developmental disorder, and the extent of the deficit is recorded. The child's behavior is very important to observe during the physical examination. The pediatrician's impression of the child can uncover issues that make this patient more psychologically vulnerable during surgery and hospitalization. Factors to consider include age and temperament of the child; nature and site of the procedure (eyes have a strong emotional association); predicted degree and duration of postoperative pain, discomfort, or disability; and length of time spent in the hospital for this procedure and past procedures.2

TIMING OF SURGERY

Elective surgery may be deferred or scheduled earlier depending on numerous factors: type and extent of the ophthalmic problem, age of the patient, developmental level, presence of risk factors, and need for postoperative cooperation by the patient. Early treatment may provide more appropriate developmental stimulation for the infant, remove parental anxiety, or avoid parental rejection or emotional reaction to the child's condition.8

For premature children, it is recommended that elective operations be delayed until the postconceptual age has reached 55to 60 weeks, because anesthetics may depress the control center for breathing. For the fullterm infant, elective surgery should be delayed until forty-four weeks postconceptual age.9

The younger infant may not demonstrate the degree of traumatic psychological effects that is sometimes seen in the older child. Even with minor surgical procedures, a preschool child may show some behavioral disturbances for up to one to two months after the hospitalization. Insecurity, increased dependency, and disturbed sleep are not uncommon even with the best preparation, understanding staff, parental reassurance, or a calm, confident attitude. These behaviors may be avoided or shortened with good preoperative psychological preparation.

POSTPONING SURGERY AND ANESTHESIA

Pediatricians are often faced with the questions of whether to postpone surgery in the child with an upper respiratory infection. Early studies by Tait and Knight in 1987 suggested that complications from surgery are not increased by the presence of an uncomplicated upper respiratory infection (URI).10,11 However, children with productive cough, sneezing, hoarseness, fever, or rhonchi were excluded from these studies. Cohen and Cameron12 reviewed a large pediatric anesthesia database and compared the rates of adverse events in 1,283 children with a preoperative URI with 20,876 children without URI. The risk of respiratory complications was increased twofold to sevenfold if a child had a URI compared with children without URI. Children with a URI require more observation and management during the perioperative period, because general anesthesia in children is associated with an increased risk of adverse respiratory events.13

If the surgeon elects not to operate on a child with a mild URI, and the average child has between three and six viral URIs per year that require several weeks until full recovery of respiratory function, he or she may find that there is little time for elective surgery in the fall and winter months. The current recommendation is this: those children under the age of 5 years with an acute URI, with signs of fever, hoarseness, productive cough, fussiness, purulent discharge, or rhonchi should have their surgery postponed until they are asymptomatic. There is a need for continuous monitoring of blood oxygen saturation and the administration of supplemental oxygen in the recovery period for any child with a history of a recent URI because of the potential for residual atelectasis or reactive bronchospasm, laryngospasm, epiglottic edema, atelectasis, and pneumonia. However, the older child with isolated naso-pharyngitis with no signs of systemic or lower tract disease can probably undergo minor elective surgery without increased risk.13

LABORATORY TESTS

Preoperative assessment should not have to include routine laboratory tests in healthy children having elective outpatient ophthalmic surgery if the child is followed routinely by their pediatrician and has a normal history and physical exam.14 The value of preoperative screening tests versus their cost-effectiveness has been examined. In healthy children, results of routine laboratory screening tests have not altered decisions on whether or not to perform surgery. A hemoglobin of 10 g/dL or higher may be the only test required by some anesthesiologists to assure a minimum level required for general anesthesia.5,15 Normal hemoglobin level varies widely with age throughout infancy and childhood. In infants 8 weeks old, the lower limit of normal is 9.8 g/dL in full terms, and 7.0 g/ dL in preterms.4 Unless significant blood loss is anticipated, a hemoglobin level lower than 10 g/dL is acceptable.5 When the hemoglobin is lower than normal, the most common cause of anemia in young children is iron deficiency anemia. Iron deficiency can be treated with an oral supplement prior to an elective procedure. In older children, an evaluation must differentiate among blood loss, hemolysis, or the anemia of chronic disease. A hemoglobin and sickle cell screen should always be done for ethnic groups at risk.14 In patients in whom a white blood count determination is indicated (recent infection, lymphadenopathy and so on), the acceptable reference range is 2,400 to 16,000.9

Urinalysis is not recommended as a routine screening test.16,17 Urinalyses are costly, and the yield of important findings is small. Mitchell looked at 732 screening urinalyses in 2695 hospital admissions and found only 6 patients with urinary tract infections in the 20% of the urinalyses that were abnormal. Most of the abnormal results were not evaluated further.16 OConnor17 found 15% abnormal urinalyses in 486 children admitted for elective surgery. In only 2 cases was the abnormality important enough to cancel the operation and neither child was later found to have significant urinary tract disease.17

A chest x-ray film should not be routinely obtained in apparently healthy children. As the value of screening tests is dubious at best, what are the disadvantages? Abnormal test results from an asymptomatic patient may not indicate disease.18 Additional tests are necessary in follow-up if false positive results are obtained. The need for additional referral is not cost-effective and can cause confusion and delay of the operating room schedule. This can produce great anxiety in the patient and family.

It is important to remember that the results of the history and physical examination should dictate what laboratory tests need to be obtained. In the majority of children who have their operations cancelled, the reason for the cancellation is due to abnormalities uncovered by the history and physical exam, not by laboratory studies.

SUBACUTE BACTERIAL ENDOCARDITIS PROPHYLAXIS

The ophthalmologist can expect to see more pediatric patients requiring antimicrobial prophylaxis because survival of children with congenital heart disease has improved. Cardiac malformation is the major factor predisposing to infective endocarditis. Although dental procedures constitute the most frequent antecedent event prior to endocarditis, other minor procedures, including manipulation of the respiratory tract can also lead to endocarditis.

Antibiotic prophylaxis is recommended to prevent subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) for procedures associated with a high frequency of bacteremia or for patients who have had a previous episode of infective endocarditis. Endotracheal intubation alone is not universally viewed as an indication for prophylaxis against bacterial endocarditis. It is suggested that you consult your institution's anesthesiology department for the standard of care in your institution.

Prophylaxis against subacute bacterial endocarditis before and immediately following a procedure is recommended for patients with cardiac disease. Cardiac conditions for which SBE prophylaxis is required include the following19,20:

Valvular heart disease

Prosthetic heart devices

Idiopathic hypertrophic subaortic stenosis

Mitral valve prolapse with regurgitation

Cardiac transplant (possibly)

Congenital heart disease (except for isolated secundum atrial septal defect)

Patent ductus arteriosus (less than 6 months following repair) Atrial septal

defect without patch (less than 6 months following repair)

The most recent American Heart Association recommendations for dosages

for antibiotic prophylaxis are summarized elsewhere in this text.

THE COMPLICATED PATIENT

The Asthmatic

In the last fifteen years the frequency of asthma has increased from 6% to 12%.21 The reasons for the increase are yet to be explained, but pediatricians are treating an increasing number of asthmatics. Pediatric surgery will also be performed on a larger number of asthmatic children, and this must be appreciated for proper monitoring during surgery and anesthesia. The risks of ophthalmic surgery for children with asthma depend on the severity of the asthma, the degree of control of the asthma, and the prevention of postoperative pulmonary complications.

The following are three main concerns regarding surgery and the asthmatic patient:

- Coverage for the patient on steroids

- Treatment for the child with an acute asthmatic episode

- Maintenance medication for the patient with chronic daily mild wheezing

As a rule, asthmatics who continue their regular medication and have optimal bronchodilation do well under general anesthesia. The asthma patient who has been treated with corticosteroids within 6 months before surgery, however, may have compromised pituitary-adrenal axis responsiveness and needs supplemental corticosteroids prior to surgery. Also, the patient on long-term, low-dose, corticosteroids requires preoperative steroid supplementation. Chronic treatment with corticosteroids interferes with the stress response, especially if surgery entails an unforeseen complication. Data that examine the effects of the use of inhalation steroids on the asthmatic are not as clear. Even though studies suggest that cortisol levels are normal in patients on inhalants, some data suggest that when these patients are stressed, their response is not completely normal. The significance of this problem depends on the dose and length of time the steroid inhalant was used.22

The preoperative physical examination should search for tachypnea, cough, expiratory wheezing, increased anterior-posterior diameter of the chest, use of accessory muscles, and retractions. All patients with asthma should have a chest roentgenogram prior to surgery.23 In severe asthmatics, an arterial blood gas determination should be considered to evaluate any hypoxemia and to assess pulmonary function in the child too young to cooperate with pulmonary function studies.

Should you cancel surgery for the patient with an acute episode of mild wheezing? Since wheezing is frequently triggered by a viral infection, this may be the best approach if cough, fever, and rhinorrhea are present. The asthmatic patient must continue to receive his usual dose of maintenance bronchodilator unless the child is in remission and demonstrates normal pulmonary function. The child with moderate to severe asthma requires additional involved preoperative preparation, including clearing of secretions. This may necessitate admission the night before the surgery. Do not discontinue either inhaled medication or long-acting medication. Information on the management of children with asthma during and after anesthesia occurs elsewhere in this volume.

The Premature Infant

Ophthalmic surgery for the premature infant is a special situation. It requires additional assessment, preparation, information, and monitoring during the administration of anesthesia, surgery, and in the immediate postoperative period.

The premature and the older former premature infant has had to face a challenging period of adjustment to extrauterine life. The premature birth of a child may result in severe immaturity of the pulmonary, cardiovascular or neurologic functions, and problems related to these systems must be anticipated. Problems of concern to the pediatrician, anesthesiologist, and ophthalmologist include chronic lung damage from residual bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), apnea, or bradycardia of prematurity; circulatory abnormalities that may require surgery, such as an open patent ductus arteriosus; intraventricular hemorrhage that extends into the brain (IVH); feeding and nutrition problems affecting growth, liver function problems and hyperbilirubinemia; susceptibility to infection; and altered healing responses.

The premature infant under 6 months of age born at less than 36 weeks' gestation is at higher risk for post anesthesia and postoperative apnea, periodic breathing, arterial oxygen desaturation, bradycardia, and cardiac arrest.9 More discussion of the premature and postoperative care occurs elsewhere in this volume.

The Child with Down Syndrome

The child with Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21) may have special medical problems that the pediatrician needs to pay particular attention to. The presence of medical problems that may increase anesthetic or operative risk should be evaluated prior to surgery. The three most significant areas of assessment are the cardiac status, the cervical atlanto-axial joint, and the midfacial area, particularly sinuses, ears, nose, and throat.

The incidence of cardiac anomalies in Down syndrome is reported to be 30% to 60%, and it is now recommended that all infants with Down syndrome have a cardiac evaluation, including an EKG and an ultrasound study of the heart, even if they do not have an audible heart murmur. If your patient has not had a cardiac evaluation, then a preoperative EKG and echocardiogram are indicated. Also consider providing for SBE prophylaxis in a Down syndrome child with a significant cardiac lesion (except for an isolated secundum atrial septal defect).20

Intraoperative complications involving compression of the cervical spinal cord are always a theoretical possibility. Because most individuals with Down syndrome have some ligamentous laxity that can affect the cervical spine joint spaces, instability of the joint between the first and second cervical vertebrae could place the spinal cord at risk for injury due to subluxation. As stated in the Guidelines for Screening for Atlanto-axial Instability revised and approved January 28, 1991, by the National Down Syndrome Congress, all children with Down syndrome should be screened before any surgery that will require intubation of the airway, as there have been rare reports of neck injury during placement of the endotracheal tube. Asymptomatic atlanto-axial instability (AAI) is found in 13% to 14% of Down syndrome individuals, and symptoms that require treatment occur in 1% to 2%. Individuals with asymptomatic AAI should avoid activities that may hyperextend the neck. Most physicians who are knowledgeable about Down syndrome children recommend that all such children be screened with lateral x-rays of the cervical spine in flexion, extension, and neutral position during the preschool years.24 If your patient has not had a screening x-ray of the cervical spine, it must be done prior to anesthesia and surgery. During anesthesia, patients with asymptomatic AAI should not have excessive extension of the neck.

Ear, nose, and throat problems associated with down syndrome are almost a universal finding. They may arise secondary to the anatomic changes associated with Down syndrome, or they may be related to the immune system defects. The major medical issues include increased frequency of sinus, nasopharyngeal, and ear infections, hearing loss, and obstructive upper airway problems. Tonsil and adenoid tissue hypertrophy as well as relative macroglossia may lead to obstructive sleep apnea.25

Other medical conditions found with higher frequency in Down syndrome patients may or may not affect anesthesia and surgical risk but should be reviewed preoperatively. Thyroid disease (found in 35%), malabsorption (35% have trouble absorbing vitamin A), nutritional problems (especially poor weight gain in the infant and obesity in the school age child), and a higher risk for leukemia are included. Laboratory screening for thyroid hormones T4 and TSH, vitamin A, and complete blood count are usually done yearly in all children with Down syndrome. If the patient has not had these studies done within one year, he or she should have them as part of the preoperative studies.26

Cerebral Palsy

The child with cerebral palsy or neuromuscular disease may have difficulty with increased salivation, seizures, spasticity of the neck and jaw, and constipation due to low abdominal muscle tone. Patients affected by this static neurologic condition should be covered with their appropriate anticonvulsant medication. Providing frequent suctioning to clear secretions and monitoring with chest physiotherapy postoperatively is often necessary.

The Diabetic

When evaluating the diabetic child prior to elective ophthalmic surgery, there are two main concerns: prevention of hypoglycemia, especially under anesthesia, and prevention of ketosis and diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) from the stress of surgery. A pediatrician as well as a surgeon should combine their efforts to provide care for the young diabetic in the hospital. If the child with type I diabetes mellitus is resisting care or if the level of blood glucose is difficult to control, admission the day before surgery is recommended. Issues to consider in preparing the patient of surgery are achieving optimum metabolic control, reviewing previous control, providing medical care and stressing compliance with treatment, and finally, evaluating any complications related to the patient's diabetes.

Most diabetologists advise specific guidelines to prepare the child, starting the day prior to surgery. The child should eat the usual diet and receive the usual insulin dose(s). The juvenile diabetic patient should be admitted the day or evening prior to surgery with the goal of maintaining or loading carbohydrates to increase the blood sugar so the risks of developing hypoglycemia are minimized. Glucose administration should be accomplished by giving a late night snack or infusion IV glucose overnight starting at 10 PM. The calories of glucose provided should be calculated based on the glucose ingested in a normal breakfast. In addition, the diabetic patient should be placed first on the operating room schedule or if this is impossible, surgery should be performed as early in the morning as possible.

Preoperative insulin doses should be adjusted to include only two thirds of the usual NPH dose and none of the regular insulin. During surgery, intravenous (IV) glucose should be continued, and blood glucose should be monitored frequently so that insulin doses can be adjusted.27 Monitoring the blood glucose in the operating room and recovery room with visual reading of test strips is accurate if performed by a well-trained individual.28

The stable diabetic child undergoing elective ophthalmic surgery needs a preoperative blood glucose determination and a urinalysis in addition to a routine history and physical examination. Surgery should be postponed if the blood glucose level is extremely high or if ketonuria is found. In an otherwise stable diabetic child who is well known to the primary physician and has reasonable diabetic control, surgery can be performed safely if enough time for a thorough evaluation and preparation is allowed.28

CONCLUSION

This section has reviewed the preoperative evaluation of both healthy children and those with complications prior to ophthalmic surgery. The pediatrician or family practitioner must provide clearance for the patient and communicate this plus the baseline status and any special circumstances to the anesthesiologist and ophthalmologist. This history, physical examination, and behavioral observation provide vital information to prepare the child and family for safe, successful ophthalmic surgery.