TOTAL CONJUNCTIVAL FLAP

The basic technique for total conjunctival flap surgery is that described by Gundersen in 1958.2 This method stresses dissection of the conjunctiva from Tenon's capsule to form a thin flap. Gundersen and others also stressed the importance of releasing tension on the flap and removing corneal epithelium so that the tendency toward flap retraction is minimized.2,5

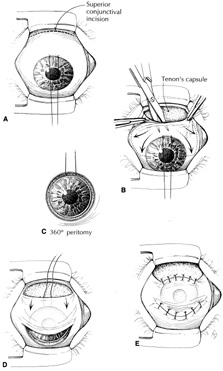

A total flap, by the Gundersen technique, may be done easily with retrobulbar anesthesia, although subconjunctival anesthetic injection may be sufficient. The corneal epithelium should be removed in all areas that are to be covered by the flap. Topical cocaine or absolute alcohol may be useful to loosen adherent epithelium.26 Residual epithelium may lead to cyst formation beneath the flap. The flap also does not adhere in areas with intact epithelium. A silk traction suture then may be placed in the peripheral cornea at the 12 o'clock position, or in the superior fornix (Fig. 1A). The conjunctiva may be ballooned with local anesthetic with epinephrine to help separate Tenon's capsule from conjunctiva. The injection should be placed so that a hole is not made in the area of conjunctiva that will cover the cornea. Maguire and Shearer described a variation of anesthetic injection beneath the superior peritomy in a series of radial needle passes followed by scissors dissection.27 Another variation, to increase the area of conjunctiva available, is to evert the upper lid over a Desmarres retractor and inject anesthetic prior to incising along the superior edge of the tarsus.28

The second step may be either a peritomy or a superior conjunctival incision (Fig. 1B). The superior incision is preferred because the limbal attachments help stabilize the conjunctiva during dissection. The superior incision should be made 14 to 18 mm above the superior limbus to allow for conjunctival shrinkage.26,27 The area of the cornea is less than 1.5 cm2, and that of the whole conjunctival sac is estimated to be 16 cm2.29 Lauring and Wergeland estimate the superior conjunctiva to provide up to 6 cm2 for corneal coverage.28 Although this may appear initially to be an abundance of tissue, the conjunctiva often “shrinks” after dissection and may be diminished by scarring. The area of dissection must be considerably greater than the area to be covered to allow movement of the flap into position without tension causing it to retract. The superior incision is made horizontally for about 2 cm. Dissection is then carried to the limbus, carefully separating conjunctiva from Tenon's capsule (see Fig. 1B). The conjunctiva should be handled gently with blunt forceps. Blunt-tipped scissors also help to avoid conjunctival perforation. Dissection is carried to both sides of the cornea to free the conjunctiva at the 3 and 9 o'clock positions (Fig. 1C). When the limbus is reached, a 360-degree peritomy is performed. In addition, the inferior conjunctiva may be freed from Tenon's capsule. Relaxing incisions may be necessary to allow the conjunctiva to be pulled down easily.

After the conjunctiva is free enough to set in place over the cornea without traction, it is secured by a row of interrupted or mattress sutures inferiorly and superiorly (Figs. 1D and 1E). Suture bites should include underlying limbal or episcleral tissue. The superior edge is secured to the episclera, leaving the donor bed uncovered. Sutures of 8-0 silk, 6-0 to 8-0 chromic gut, 8-0 Vicryl, and 10-0 nylon have been used. Nonabsorbable sutures may be difficult to remove.

Among the variations of a total conjunctival flap is combination with lamellar keratectomy. This may be done to remove ulcerated necrotic tissue, improve adhesion of the conjunctiva, or “inlay” the conjunctiva. The use of a lamellar keratectomy to allow a flat conjunctival surface is most helpful for peripheral partial flaps.16 It is also possible to pull the conjunctiva over the cornea without dissection by placing sutures in the superior and inferior fornix, drawing the conjunctival fornices together over the center of the cornea, and suturing these “everted” flaps over the cornea.30 Such flaps retract within a few weeks but may be helpful in situations where more refined techniques are not feasible.

ADVANCEMENT FLAP

A partial flap may be performed in the same manner as a total flap, but covering only a portion of the cornea. If the area to be covered is peripheral and small, the peritomy alone may be used to incise the conjunctiva, sliding the conjunctiva as a “hood” flap. However, simple advancement flaps often retract with time.

PEDICLE FLAP

Pedicle flaps may be fashioned from perilimbal or superior conjunctiva to cover localized defects.31 The area to be covered is measured and the conjunctival dissection made about one-third larger. Because these flaps are sutured directly to the cornea, 10-0 nylon sutures are used. When the corneal defect is peripheral a single-pedicle (racket) flap is used, whereas a bipedicle (bucket-handle) flap is used for central or paracentral lesions.32